2024 celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of Lucy (24/11/1974), the name given to the now-famous hominid skeleton discovered in Hadar, in the Afar region of Ethiopia.

This discovery paved the way for a wealth of research and field surveys that continue to enrich our knowledge of the evolution of our ancestors. Since then, considerable progress has been made, with new fossil remains belonging to several hominin species (including Australopithecines) having been found in the Ethiopian Rift.

Between 1966 and 1973, a fossil deposit in southern Ethiopia, in the lower Omo valley near the Kenyan border, was prospected by international multidisciplinary teams. Yves Coppens is leading the major French palaeontological expedition there, in conjunction with two British and American expeditions. Scattered fossil remains of hominids were found, including teeth, bone fragments and skulls (in East Turkana). They indicate the presence of Australopithecines in the northern tropical hemisphere from 2.5 Ma. Yves Coppens successfully publicised the Omo expedition. At the dawn of a brilliant career that began at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, he was already famous when the first hominins were discovered in Afar, and his talent as a lecturer, communicator and author made "Lucy" a veritable myth of the origin of Humanity.

Maurice had discovered major sedimentary deposits in the lower Awash valley and needed to know their age in order to draw up a geographical and geological map for his thesis. From 1971 onwards, Maurice Taieb and Jon Kalb travelled and prospected together the immense territory of the nomads in virtually unknown regions. They discovered the extent of the sedimentary outcrops of the Rift and numerous fossil and carved tool deposits.

In 1971, Maurice Taieb brought back an elephant jawbone recognised by the palaeontologist Yves Coppens as belonging to a species, Elephas reckicharacteristic of the oldest strata in the Omo Valley palaeontological deposit, which was the subject of the first K/Ar dating.

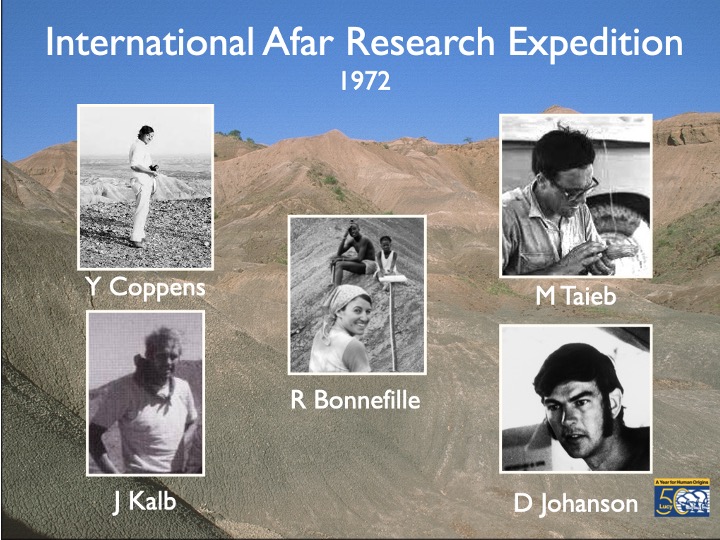

In May 1972, Maurice invited Yves Coppens and Donald Johanson on a short tour, during which they reached Hadar. The abundance of fossil animal bones of all kinds, spread over an immense area, was breathtaking. On their return to the capital Addis Ababa, they set up the IARE (International Afar Research Expedition), which included Raymonde Bonnefille and Jon Kalb.

The first expedition to Hadar took place in autumn 1973. Motivated by the desire to find something, by the fascination of the unknown, and by a respectful understanding of each other's talents, the expedition of four doctoral students forged ahead, enthusiastic despite the difficulties. In December 1973, Donald Johanson located the bones corresponding to the knee joint of a standing Australopithecus.

From this first discovery, the scientific interest, quickly understood in the United States, and the numerous conferences enabled Donald Johanson to obtain substantial funding to continue prospecting.

In 1974, other American geologists and French prehistorians and palaeontologists joined the team. It had more equipment at its disposal, including Ethiopians from the Addis Ababa Museum. Donald Johanson and Tom Gray located the various parts of Lucy's skeleton, scattered on the surface, on the slope of a hill at locality 288. Maurice Taieb then enlisted the help of other geologists to establish Lucy's age at 3.2 Ma... and support his thesis!

This was followed by two fruitful years during which Maurice directed and organised the camps. Prospecting came to a halt in 1978, following the political and administrative changes that took place in Ethiopia with the end of the imperial regime. They were resumed in 1990, exclusively by the Americans, led by Donald Johanson, then B. Kimbel, supported and funded by the Institute of Human Origins.

They continue to this day, supplemented in neighbouring regions by those undertaken by other American and Ethiopian researchers. For half a century, the many discoveries in the Ethiopian Rift Valley have been a tribute to Maurice Taieb, the pioneer and discoverer of this Eldorado of archaeological and anthropological research.

Raymonde Bonnefille is a palaeopalynologist and CNRS research director emeritus.

Bold and daring, he ventured into the Afar region for his thesis in the 1970s in search of larger, older deposits.

Maurice travelled through difficult regions, with a remarkable sense of spatial awareness. He knows how to live in spartan conditions and make friendly contact with desert nomads like no one else. It was an Afar shepherd who pointed out the area where he had seen bones.

Bibliography

Taieb M. 1985 : " On the Land of the First Men "When geology becomes an adventure. Paris Robert Laffont.

Bonnefille R. 2018 : " In the footsteps of Lucy "Expeditions to Ethiopia. Paris. Odile Jacob.

Note by Raymonde Bonnefille, DR CNRS, young researchers

"By retracing this history, which for some is mythical, I hope that it will be a source of inspiration. Young researchers can always discover new things. That's the great thing about our job at the CNRS. In the geological field, following in Maurice's footsteps, there are still some unknowns to elucidate, which may be less publicised but are just as interesting. Prospecting The palaeoanthropological studies concern geographically limited territories and are not placed in the more general geological context of the temporal evolution of the Rift over the last 10 million years. We do not have an overall view as initially envisaged by M. Taieb and J. Kalb. For example, with all the volcanic ash dating now obtained, there is no geological map of the distribution of deposits over the entire Rift. At what altitude was it at the time of occupation by the first australopithecines? How did the succession of sedimentary deposits take place, with a single initial lake, later fragmented into several lakes moving from south to north? What was the respective role of tectonic movements and climatic changes? Why and how did this region remain the favourite domain of Australopithecines between 4 and 3 million years ago? These are just some of the issues that could be addressed in future hominin surveys.

Good luck to future researchers.